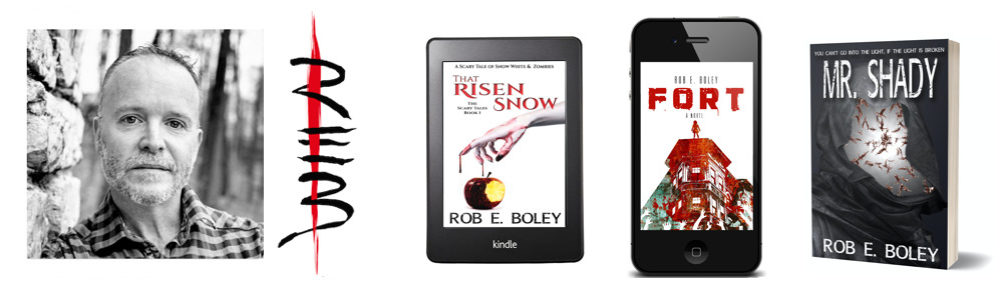

The other day, a reader sent me a message via Twitter complimenting me for a scene from my first book, That Risen Snow.

The other day, a reader sent me a message via Twitter complimenting me for a scene from my first book, That Risen Snow.

Shameless plug: That Risen Snow is now on sale for free in ebook format on Amazon, BN.com, and most other online retailers.

I’ll avoid any spoilers, but basically the scene involves a character revealing that he’s been infected by Snow’s zombies. This character is trapped inside a mine with the other characters, and has basically become a ticking time bomb.

One of the things this reader liked about the scene was my use of onomatopoeia. Throughout the scene, the zombies can be heard in the background digging through some rubble.

Tchk. Tchk. Tchk.

Until I received this message, I hadn’t really thought all that much about how or why I use onomatopoeia. But now that I think about it, I do it a lot! In fact, the current novel I’m working on uses this device a lot.

Tchk. Tchk. Tchk.

I do other stuff, too, to visually cue the reader. For example, if I have a character falling, then I let the words fall, too.

One after another.

And another.

Dropping.

Hitting the return key.

And return again.

Tchk. Tchk. Tchk.

Or alternately if I want to create a sense of claustrophobia, then I’ll make a very dense block of text or if I want to create a sense of rambling confusion then I’ll just have one run-on sentence that goes on and on sometimes erratically like in two hours I need to have another meal or I wonder if my oil change is done or sometimes if I want both claustrophobia and confusion then I’ll do both at the same time.

Tchk. Tchk. Tchk.

My point here is that—as writers—words are our tools. And while primarily they should be used as subjects, verbs, and adjectives and neatly arranged in paragraphs, they occasionally can have other uses. We can work with our tools, but we can play with them, too. The Word Police won’t come after you if you use a word other than it was intended.

Remember, words are read, but they are also seen. And sometimes they’re just out of sight, lurking, waiting, scratching to get in.

Tchk. Tchk. Tchk.